Tommy (right) and his brother, John S. O'Connor, in Volunteer uniform

In the centuries, old struggle for Irish independence from the British Empire, many men have had their names enter into the folklore of the Irish fight for freedom; From Red Hugh O’Donnell, Owen Rowe O’Neill, Theobald Wolfe Tone and Robert Emmet to the more modern figures of Padraig Pearse and James Connolly, these men have been revered to the point of becoming almost mythical figures in the process. But what of the men and women whose names are not sung in rebel songs and discussed in the history of famous rebellions? No less important to the cause, they were the people happy to quietly work towards the goal of independence while others took the limelight. Thomas D. O’Connor was one of these figures. In fact, O’Connor spent his life trying to avoid detection, a trait which he maintained right up until his death in 1955. For he was the IRB’s trans-Atlantic courier.

A Courier’s Tale

Thomas D. O’Connor was born on January 31st 1895, at 5 Mount Pleasant Avenue in Limerick. He was the fifth of seven children, and the second of three boys, born to Thomas Joseph O’Connor and Helena Maher O’Connor. Tommy’s early years were spent in the family’s native Limerick but by 1901, the O’Connor clan had moved to Dublin’s North Inner City settling on Lower Sherrard Street, first sharing the house at number 7 with three other families, before moving to their own premises at number 4.

Having come from a family which held strong nationalist views, it appears Tommy, along with his younger brother John S. O’Connor, was always destined to play his part in the struggle for Irish independence from Britain. His father, Thomas Snr, and aunt Brigid had been founding members of Sinn Fein in 1905 and the brothers would no doubt have been swept up in the Gaelic Revival of the early 20th Century, which created a wave of nationalist feeling throughout Ireland. As a young boy, Tommy was a member of Na Fianna Eireann, the republican boy scouts, who were founded in 1903 by Bulmer Hobson. No doubt his republican views were solidified during this time, as evidenced by the oath which all the boy scouts took upon joining the Fianna; “I pledge myself to fight for the independence of my country, never to join the British Army, Navy or Police and to obey my superior officers.”

As O’Connor himself mentioned in his short Bureau of Military History Witness Statement, he “[had] been associated with the separatist movement from his early teens – from the commencement of the century”, so it is no surprise that he would eventually take a more active role in the cause of Irish independence. But, it is perhaps more surprising how he found himself in such a vitally important role to the movement.

A Night to Remember

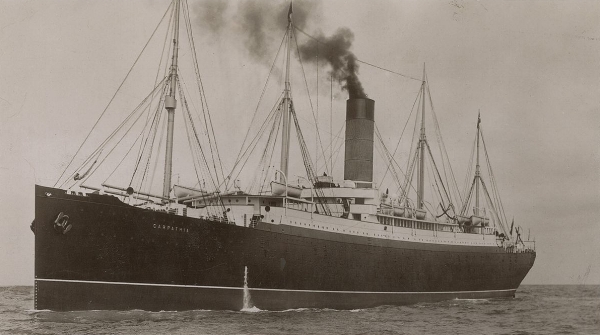

RMS Carpathia, which went to the rescue of the sinking Titanic on the night of April 15th, 1912

While it is unclear exactly when Tommy began working as a crewman on the ships crossing the Atlantic, it is certain that by 1912, he had established a fledgling career as a seaman. Family history suggests that he left Ireland for Liverpool, and his new career, following a falling out over an argument he had with his father. What is clear however, is that this course of action would change Tommy’s life forever.

On the night of April 15th, 1912, he was working as a scullion onboard the R.M.S. Carpathia when it received a distress signal from another vessel travelling in the North Atlantic. The famed ocean liner Titanic had been involved in a collision with an iceberg 300 miles south of Newfoundland and was sinking fast. The Carpathia rushed to the aid of the stricken vessel and began rescuing as many survivors as it could while the ship continued to sink. Over 700 people were rescued from the Titanic that night and as a crewman working in the kitchen, Tommy was no doubt kept extremely busy throughout the rest of the voyage. Along with the other crewmembers of the Carpathia, he received a bronze commemorative medal in recognition of his efforts in the rescue. High ranking officers were presented gold medals, lower ranking one’s silver and crewmen received bronze medals from a group of wealthy survivors led by “The Unsinkable Molly Brown”.

Were it not for the grandchildren of Thomas D. O'Connor, and the amazing research that they uncovered, the story of the Irish Republican Brotherhood's Trans-Atlantic Courier might have been lost to the annals of time. In this short documentary on the life of one of Irish-America's forgotten patriots, his son Tommy and grandchildren, Tommy Vogt and Ellen Eisenstein, recount the amazing journey of their not so famous relative.

Working for ‘the cause’

Although Tommy and his family were staunch republicans, it is unclear as to when exactly he began taking an active role in the nationalist movement but, in February 1914, he joined the Irish Volunteers and, in July of that year, took part in the Howth gun-running along with his brother John. By that time, Tommy had been back living with his parents in Dublin and was employed as a clerk in the offices of Lynch & Deering Solicitors. In his military service pension application Tommy states that “shortly after the commencement of the war in August 1914, the late Thomas J. Clarke and Sean McDermott, with whom I was intimately acquainted, requested me to leave my employment and obtain a position of some kind on an Atlantic Liner travelling between Liverpool and New York, in order to establish regular and reliable communication with the Clan na Gael in New York”. Clarke and McDermott were no doubt aware of Tommy’s previous work on the trans-Atlantic liners, and of his Carpathia medal, and understood that this was a unique opportunity to have an agent that was unknown to the British act as the key link between Ireland and America. Tommy resigned from his promising position with Lynch and Deering and moved to Liverpool in early November 1915, changing the course of his life forever. He was sworn into the Liverpool circle of the IRB by its ‘centre’, Joe Gleeson, and began a new and dangerous chapter in his life.

Having been a member of the crew on the famed Carpathia, Tommy had no trouble gaining employment on the ships crossing between Liverpool and the United States, and he would take whatever position he could get on boards these vessels. His orders were to keep the lines of communication open between the IRB and the Clan na Gael in New York, where his contacts were John Devoy, Joe McGarrity and John Ryan. Between November 1915 and April 1916, Tommy carried highly confidential messages between the Irish leaders on both sides of the Atlantic and often returned with vast sums of cash and gold that would be used to fund the fight against the British. It has been estimated, by John Devoy, that in the first number of months of 1916, over $100,000 was sent to Ireland from America, with most of that figure being carried by Tommy O’Connor.

It is a testament to the high regard that Tommy was held in by the IRB’s leadership that he was tasked with carrying many highly sensitive messages in the lead up to the Rising. He not only travelled between Ireland and America in this capacity, but was also sent to Germany several times to liaise with Roger Casement, who was trying desperately to secure support from the German government for an armed insurrection against the British. In January 1916, Tommy met with Casement in Germany to inform him that an uprising was imminent and that arrangements would need to be made with the Germans immediately if they were to aid the Irish cause. Michael J. Kehoe, a Lieutenant in Casement’s failed Irish Brigade in German POW camps, remembered O’Connor’s visit in his Bureau of Military History statement given in 1952;

“[O’Connor] asked Casement if it would be possible to send a courier to Ireland in a submarine when arrangements had been completed by the German authorities for the landing of arms and men on the Irish coast. This courier was to bring full particulars regarding the landing arrangements. Casement said that he would endeavor to do this when he knew something definite. “

Having stressed to Casement that the German authorities would need to expedite their plans to support an Irish insurrection, Tommy returned to America to update John Devoy on the plans for landing German arms off the Kerry coast. Not long after meeting with Devoy, O’Connor would once again cross the Atlantic to Liverpool where he met with Piaras Beaslai, who had a number of messages to pass on to the Clan na Gael leadership. Beaslai, a few days earlier in Dublin, had been given a small pocket notebook by Seán MacDiarmada which contained a coded message that stated the date had been set for the insurrection against the British. It was to begin on April 23rd, Easter Sunday, 1916.

A Very Important Message

On February 5th, 1916, Tommy arrived unannounced at the offices of the Gaelic American in New York, looking to speak to John Devoy about a matter of extreme urgency. Devoy brought O’Connor around the corner to the busy Haan’s Restaurant on Park Row, where he was handed a sealed envelope from Dublin. The message inside read;

“This message is to be read only by members of the Revolutionary Directory. We have decided to begin action on Easter Sunday. We must have your arms and munitions in Limerick between Good Friday and Easter Saturday. We expect German help immediately after beginning action. We might be compelled to begin earlier.”

What happened in the time between Tommy delivering this message and the beginning of the Rising, turned into one of the biggest “what might have been” moments in Irish history. In a cruel twist of fate, Tommy had begun his voyage back to Ireland prior to the arrival of another courier sent by the IRB. On April 14th, Philomena Plunkett, sister of Joseph Mary Plunkett, arrived at Devoy’s offices with another coded message from the Military Council of the I.R.B. stating that the German arms were not to be landed before Easter Sunday, April 23rd. Unfortunately for all involved, the ship carrying the German munitions, “The Aud”, had left Germany on April 9th and, like most cargo ships at the time, had no radio on board on which to relay the message. To make matters worse, Tommy was already onboard a trans-Atlantic liner on his way back home to deliver a message that re-affirmed the original dates for the landing of the guns. Before the Rising had even begun, it was looking like it was doomed to fail.

On the 19th of April 1916, the Wednesday before the Rising started, Tommy arrived back in Dublin carrying a coded message that he would later describe to his brother Johnny as being “the most important message ever brought to Ireland”. He immediately went into a long conference with Tom Clarke and Seán MacDiarmada informing them that the original timeframe for landing the German arms could not be changed. Knowing that there was now even less hope for a successful insurrection to take place, the IRB’s supreme council decided to nonetheless go ahead with the Rising.

The night before the Rising began, Tommy acted as Tom Clarke’s personal bodyguard at his home in Fairview, Dublin. Tom Clarke had wanted Tommy to return to America before the rebellion began as he considered him to be too valuable an asset to be lost but O'Connor refused and the Volunteer leader reluctantly gave him permission to take part in the insurrection. Years later, Kathleen Clarke in her book Revolutionary Woman, would write about what was to happen that night if the British authorities arrived at the house she shared with her husband;

“Tommy O’Connor and Sean McGarry were to act as Tom’s bodyguards, and were to stay in the house for the night. They decided that if there was a raid on the house, and any attempt to take them prisoner, they would not surrender. They were to fight and die rather than that. I had a pistol and knew how to use it, and if necessary, meant to take a hand. Before going to bed, we planned what we would do in case of a raid. The hall door was in the centre of the house, with rooms on each side, and the stairs faced the hall door. If a knock came, I was to go to the door and ask who was there. If the answer was the police or military, I was to say nothing but open the door, keeping close behind it. Tom was to be in the door of the room on the other side of the hall door, and Tommy and Sean were to take up position at the head of the first flight of stairs. We were to fire at each man as he came in, and it was to be a fight to the finish.”

The night passed without incident and the next morning all three men went to their posts in Dublin City. As a member of F Company 1st Battalion of Irish Volunteers, Tommy fought under the command of Ned Daly at the Four Courts Garrison, in the areas of North King Street and Church Street, where some of the fiercest battles took place during Easter Week. On April 29th, when word of the surrender of the rebel forces reached the Four Courts Garrison, Tommy was asked by Ned Daly to undertake a dangerous mission to go and verify the surrender order with the Volunteer leadership at G.H.Q. in the GPO. Having removed his Volunteer uniform, Tommy made his way towards the Post Office but was picked up by British soldiers before he could complete his task and was sent to Richmond Barracks. He was eventually deported to Knutsford Prison in Chesire, England, before ultimately ended up in Frongoch Internment Camp in North Wales. On Christmas Eve 1916, O’Connor and the other Irish prisoners in Frongoch were released as part of a general amnesty called by British Prime Minister Lloyd George, and he returned home to Ireland.

A New Identity

It did not take long for Tommy to resume his position as the IRB’s chief agent crossing the Atlantic after his release from Frongoch. In January 1917, at the request of the Supreme Council, he travelled once more to Liverpool, and after several weeks managed to secure a position on a trans-Atlantic liner in order to resume regular and reliable communications with the Clan na Gael in New York. However, he was now known to the British authorities to be an Irish revolutionary, meaning he would have to sail under an assumed name. As Thomas Welsh, he continued his work for the Irish cause bringing dispatches between Liverpool and New York until, on November 4th 1917, he was stopped by a British agent while disembarking the S.S. Celtic on the New York docks. O’Connor was handed over to American police and was charged with an offence under the War Regulations Acts of fomenting a rising against a power friendly with the U.S. He was sent to The Tombs Detention Complex in Manhatten and held on a $2,500 bail bond. Following the arrest, William J. Flynn, Chief of the United States Secret Service, gave several press conferences about the arrest of Thomas Welsh and the alleged Sinn Fein “plots” in the U.S. The arrest made front page news across America, with the New York Times running the headline; “SEIZED LETTERS REVEAL GERMAN AID TO SINN FEIN”, in their November 11th edition of the paper.

On April 10th 1918, O’Connor went on trial and was sentenced to imprisonment for a year and a day in the United States Federal Penitentiary in Atlanta, Georgia. His legal team appealed the decision and, on April 12th, he was released pending appeal on a fixed $10,000 bail bond. For the next 3 years, Tommy and his lawyers fought to try and get his conviction overturned, taking the case through the various courts all the way to the US Supreme Court, who dismissed the case ending any hope that O’Connor had of avoiding jail time in America.

While his appeal was ongoing, Tommy continued to work as an authorised agent of the provisional government of the Republic of Ireland. While it is unlikely that he himself travelled between the US and Ireland during this time due to his legal troubles, he does state in his pension application that he “was engaged with the representatives of the I.R.B. in keeping open the lines of communication with Dublin and [also] collection and dispatch of arms”. He was employed as office manager in the bond office of the First Dáil Eireann External Loan at 411 5th Street in New York, before being appointed the Executive in charge of the bond drive for the Pacific States, Arizona and Nevada. Before being imprisoned, O’Connor also played an active role in Eamon De Valera’a US tour from June 1919 until December 1920. By this stage, the Irish-American political community was in turmoil, owing to deep divisions in the Friends of Irish Freedom and other organisations supporting the cause of Irish indpendence in America. On December 28th 1920, Tommy along with Joe McGarrity and Larry De Lacy, broke into John Devoy’s office at the Gaelic American and stole the subscription lists of the Friends of Irish Freedom, which significantly bolstered De Valera’s newly formed American Association for the Recognition of the Irish Republic.

In January 1921, Tommy turned himself into the authorities in Atlanta and began his prison sentence. Years later, in 1927, he would receive a presidential pardon from Calvin Coolidge, the 30th President of the United States, having previously been denied one by Woodrow Wilson.

Tommy was released from prison on November 13th, 1921, serving his sentence minus time off for good behavior, just as Ireland was entering one of the darkest periods in its history. Less than a month after O’Connor’s release, the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed which would eventually lead to the break out of the Civil War in June 1922. Tommy took the Anti-Treaty side of the argument and as Secretary of the American Delegation of the Irish Republican Party, he supervised the US speaking tours of Countess Markievicz and Kathleen Barry between April and May 1922, raising significant funds for the Anti-Treaty forces. In the Summer of 1922, he would begin a series of speaking engagements, critising the newly founded Irish-Free State as “agents of England”.

In December 1922, Tommy returned to Ireland with his heavily pregnant wife Frances but it was not long before he found himself behind bars once again. Writing in his military service pension application, Tommy states “I returned to Dublin in December 1922. My house was raided by the Free State Army during the night [and] I was taken away and imprisoned in Mountjoy for three months”. In March 1923, he was released from Mountjoy. As a new father, it seems that Tommy kept somewhat of a low profile in the intervening months with very little information being available as to any activities he was engaged in on behalf of Anti-Treaty forces. On October 11th 1924, Tommy and his young family returned to the United States to start a less volatile chapter in their lives. He would go on to have a long career as an adjunct professor of accounting at New York’s Pace College, as well as working for a time as the chief accountant for the Chilean government at their US embassy.

Code of Secrecy

Even though O’Connor had a somewhat unique viewpoint into one of the most important times in Irish history, he steadfastly refused to break his own strict code of secrecy at any point during his life, and divulge what can only be imagined are interesting and unknown tales from Ireland’s revolutionary period. Even years after the events, Tommy kept silent about the work he was engaged in, a fact which is illustrated when, in July 1952, P.J. Brennan, who was the Secretary of the Bureau of Military History sent him a letter asking for information about his time fighting for Ireland’s freedom. It reads;

“In view of your close association with the movement for Irish independence, in Ireland and in the United States, during the years 1916-1921 and with many of the developments of the period as well as your intimate personal contacts with a number of the leaders of the Rising of Easter Week, 1916, the Director would appreciate it very much if you could see your way to set down on record for the Bureau, with as much detail as possible, an account of your experiences during that time, and to place at the disposal of the Bureau any documents you may have in your possession…It should be told with as much detail as you can remember, including dates, persons, places, etc, as incidents which appear to be of no importance may, in the view of historians, have a real significance…I may add that the Director has had several conversations recently with your brother, Mr. John S. O’Connor, in regard to the work of the Bureau and he is satisfied that you have a very important story to tell and he is anxious that you should record it without delay for the Bureau.”

As well as receiving the letter, Tommy was also sent a long list of questions pertaining to his activities on behalf of the Irish cause, from his earliest days working the Trans-Atlantic crossings up until the end of the War of Independence. Tommy chose to mostly ignore these questions and instead wrote a short and extremely sparse account of the work he was engaged in.

While we may never know the full extent of the work carried out by Thomas D. O’Connor during his time working towards the cause of Irish freedom, what we do know about him amounts to a fascinating portrait of one of Ireland’s most important, yet least known, revolutionaries. Owing to the extensive research work of his grandchildren Ellen Eisenstein and Tommy Vogt, we possibly know more about Tommy today than he would have liked but it is important to recognise the unique work he performed on behalf of Irish freedom. Perhaps this work is best summed up by the quote below from his great friend Seán T. O’Kelly;

“It gives me great pleasure to bear testimony to the excellent manner in which Mr. Tom O’Connor carried out the most responsible, highly dangerous and difficult work which he was called upon to perform in 1915, and which he continued to execute with entire satisfaction to his superiors all during the period of the national struggle…The work Mr. O’Connor did in those years was of the most responsible kind. He could not be too highly praised for the efficient manner in which he carried it through. I know that Tom Clarke, Sean McDermott and all who had intimate knowledge of the magnificent service he was rendering ever spoke of him and his work in the most eulogistic terms. They always regarded Tommy O’Connor not only as a most trusted and efficient officer but one who by his unique services to the cause, they were always glad to speak of as a valued comrade and friend.”

- Written by Colin Farrell

- Images: Ellen Eisenstein & Tommy Vogt

- References:

- 'The Courier's Tale: A Biography of Thomas David O'Connor' by Thomas G. Vogt

- 'From Subjection to Irish Freedom: The Role of the O'Connor Brother' by Eileen Butterly

- 'Revolutionary Woman' by Kathleen Clarke

- 'Irish Rebel: John Devoy and America's fight for Irish Freedom' by Terry Golway

- BMH WS ref. #836 & #1070 (Tommy O'Connor)

- BMH WS ref. #741 (Michael J. Kehoe)